A drought in much of South America impacts more than 420,000 children living in the Amazon basin, according to a new report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef).

The ongoing climate crisis, driven by extreme heat and reduced rainfall, has caused the rivers of the Amazon—the world’s largest rainforest—to dry up, isolating communities and threatening the wellbeing of its most vulnerable inhabitants, children.

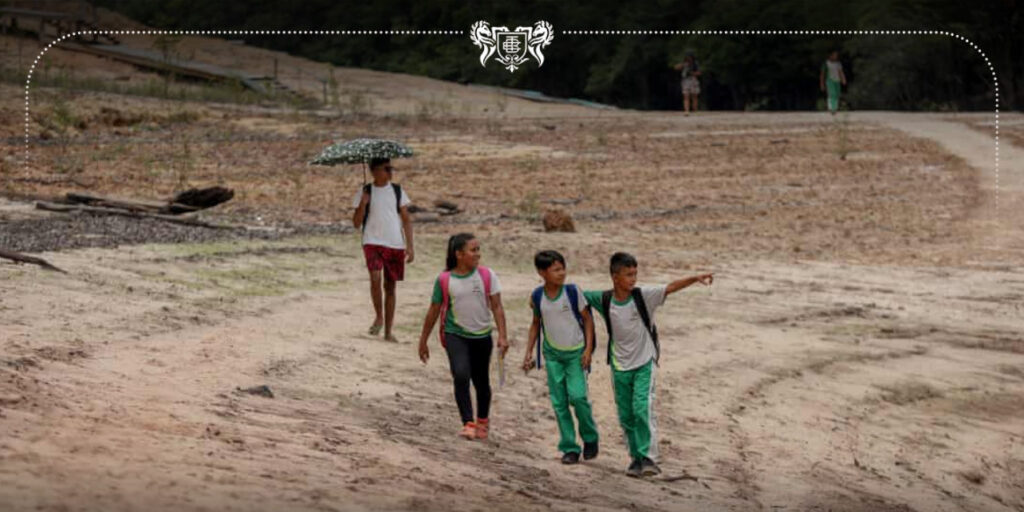

In what is traditionally the wettest region on Earth, rivers have receded to historic lows, disrupting the daily lives of millions.

The drought, worsened by deforestation and weather events such as El Niño, has led to the Amazon River and its tributaries becoming impassable.

This has severely impacted transportation for local communities, cutting off access to essential resources such as food, water, medical care, and schools.

According to the Unicef report, over 1,700 schools and 760 health centres across the Amazon region are now inaccessible due to the drought’s devastating effects. For many children, this has meant a complete halt to education and critical healthcare.

The extreme weather conditions have made it difficult for communities to access health services, and many children are suffering from preventable diseases like malaria and dengue fever.

Antonio Marro, a Unicef manager, warned that for the most remote areas, the situation has become life-threatening. “Children are contracting diseases, and there is no way they can reach a health centre for treatment,” he said.

Young children, particularly those aged five and under, are at higher risk of malnutrition, infections, and other serious health conditions.

Research has also shown that babies born during extreme droughts or flooding are more likely to be born prematurely or underweight, further compounding the crisis.

The drought is part of a wider environmental crisis exacerbated by the ongoing deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. As temperatures rise and rainfall decreases, large areas of the rainforest are left scorched, with large sandbanks replacing once-thriving rivers.

In October, two of the Amazon’s largest tributaries, the Solimões and the Rio Negro, reached their lowest water levels since records began in 1902.

The drought is also causing widespread ecological damage, with many fish species dying off and mass fatalities of pink river dolphins. Conservationists are growing increasingly concerned about the long-term impact on biodiversity in the region.

Indigenous communities living in the Amazon are among the hardest hit by the crisis. Gentil Gomez, a member of the Ticuna Indigenous community in Colombia’s Lake Tarapoto, shared the struggles faced by his community: “We rely on the river for everything, but it’s raining maybe once a month, so now it takes a long time to get to town and sometimes we just give up pushing and pulling our boats because the river is too low.”

Unicef estimates that at least $10 million is urgently required to provide life-saving aid to the most affected regions of Brazil, Colombia, and Peru.

This funding will be used to deliver essential supplies such as clean water, food, and medicines, as well as strengthen public services in Indigenous communities.

The health of the Amazon, described by Unicef’s executive director Catherine Russell as “critical to the health of us all,” has global implications.